catherio's guide to egg freezing

14 things I wish I knew before I started the egg freezing process

In 2019, I froze my eggs and wrote a guide for friends. I learned so much, and I wish I knew more about egg freezing before I started. Now I’m sharing that guide with you!

tl;dr: My overall take on egg freezing is that:

Everyone with ovaries and some interest in having kids with their own gametes should do a fertility consultation.

For me, the experience was very worth it. Overall it was about as taxing as having a very bad cold, gave me a few months of severe period cramps afterwards, and cost a few thousand dollars, in exchange for a “>90% chance of 1 kid” card, which I think was very worth it for me.

Here are the lessons I learned over the process:

Lesson 1: Fertility declines after 35

Lesson 2: You can check your fertility numbers

Lesson 3: Consultation → extraction can take a long time, depending on clinic

Lesson 4: You might need multiple cycles

Lesson 5: Freezing eggs is usually an “85% chance of 1 kid” card

Lesson 6: Ovaries go from walnut- to orange-sized

Lesson 7: No strenuous exercise!

Lesson 8: Injections are annoying, but you can do things to make them better

Lesson 9: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is a *fluid balance* problem

Lesson 10: Ask what protocol you’re on!

Lesson 11: Minimize commute time to your clinic

Lesson 12: You can use COBRA for this if you changed jobs and lost fertility benefits

Lesson 13: You can look up success rates

Lesson 14: Choose a time window when you can tolerate schedule disruption

Overall verdict - is it worth it?

My recommendation is that if you have ovaries/uterus and a non-zero interest in having kids with your own gametes you should do at least a fertility consultation, to get detailed information about your personal ovarian reserve. (See Lesson 2 for more about that)

As for egg freezing: personally in my estimation, proceeding with egg freezing might makes sense for you if some combination of these factors is true:

You learn from your consultation that your ovarian reserve is unusually low for your age, or you’re approaching 30 without specific plans to have kids, or you already know you’ll prefer to have your last kid in your late 30s or in your 40s

You’re okay with a 5% chance of medical complications

You have some way to make ~$15k not be a large financial burden (such as specific fertility benefits), or having kids with your own gametes is a very important part of your vision for your future such that it’s worth the cost anyway.

For me personally:

I had a high-ish number of resting follicles (37 follicles), so no worries there, but at the same time, I’m turning 29 this year and I don’t want kids anytime soon.

My large number of follicles put me at higher risk of complications, but my doctor selected a protocol that minimized the risks.

I was covered by Progyny fertility insurance through Google, which is a policy similar to ordinary medical insurance, thereby requiring me to hit my deductible, then pay 10% over that, capped at my out-of-pocket maximum.

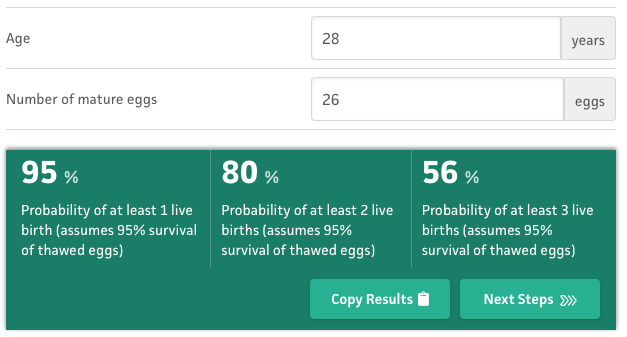

The experience overall was physically about as taxing as having a very bad cold and cost a few thousand dollars. Also, having a large number of resting follicles meant that just one cycle was enough to extract 26 eggs, which is on the high end. (For comparison, another friend I know had 7 eggs extracted in her first cycle).

In exchange for having undergone this, I now have a “>90% chance of 1 kid” card that I can play at ~any point in the future, even if my natural fertility is declining. This gives me flexibility not rush to have kids by 35 if I don’t want to.

So I think definitely worth it, for me.

Start here

If this is the first thing you’re ever reading about egg freezing, you might want to start with one of the other writeups or guides out there.

Connie Yang’s Field Guide to Egg Freezing is pretty good!

https://medium.com/@wren/field-guide-to-egg-freezing-6ef72119c9ea

That’s because my writeup here covers the extra stuff I felt was still unanswered after I read everything publicly available to me. You can start here if you want, but I haven’t made an effort to cover the super-basics.

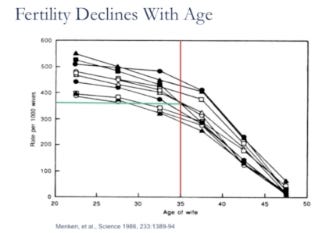

Lesson 1: Fertility declines after 35

For most folks with uterus/ovaries, fertility is stable-ish until 35, and then declines sharply until 45:

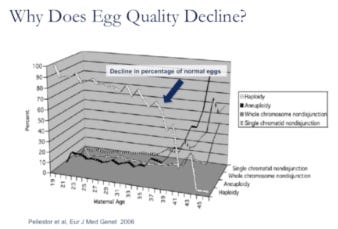

The decline is largely due to decrease in egg quality, which is mostly due to aneuploidy (abnormalities in chromosomal number).

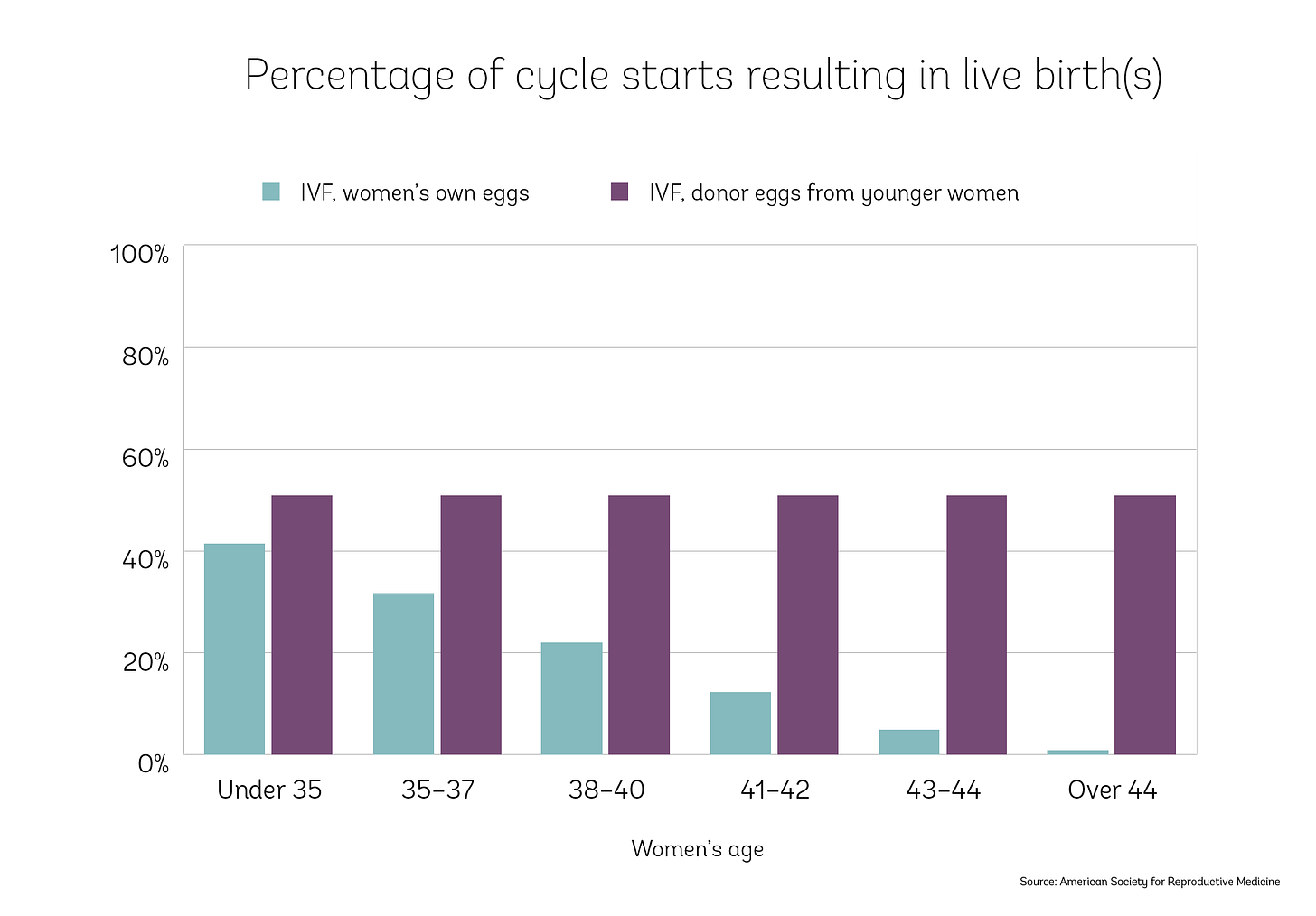

It’s not due to problems with the uterus. People over 44 can conceive with donor eggs at the same rate as people under 35:

I initially thought that these numbers meant that there’s no biological reason to freeze eggs sooner than 35, but that’s not correct. The earlier you do it, the more likely you can get away with fewer cycles than if you wait longer (see Lesson 4 for more about that). You’ll have to pay annual storage fees for more years (a few hundred dollars per year) if you freeze earlier, but I would guess that even just from a financial perspective this is outweighed by the increased chance of having to pay for additional cycles if you wait longer.

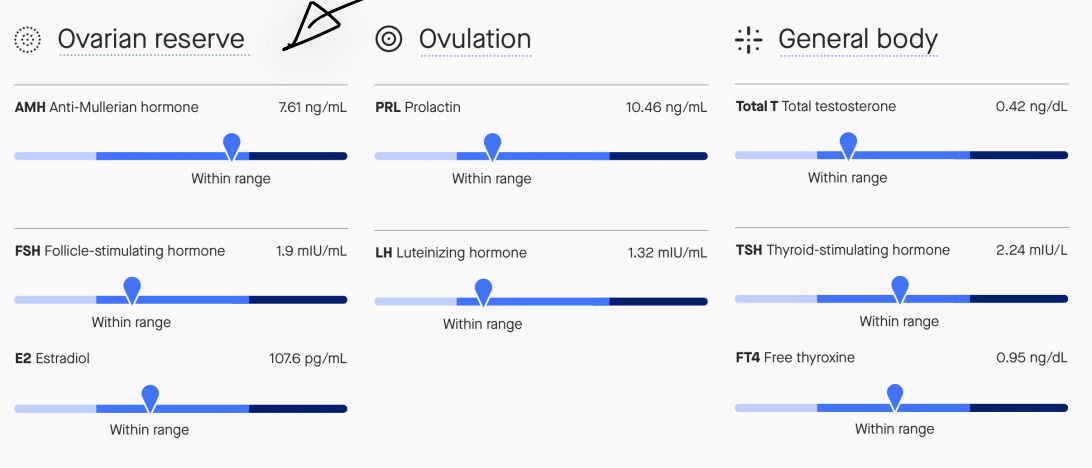

Lesson 2: You can check your fertility numbers

I had read Mason Hartman’s twitter thread, in which she discovered that she had an unusually low follicle count (and likely low fertility) for her age. She ended up having to undergo 3 cycles of egg freezing to reach her target number of eggs.

This led me to realize that I had no idea whether I was on a “normal for my age” fertility trajectory, or whether I was already facing infertility without knowing it.

Learning from the ultrasound that my resting follicle count was fairly high (37 follicles), and that my fertility hormone levels were normal, was a huge change in my attitude. I knew then that I would probably be able to have kids naturally if I started trying before 35, even if I didn’t do any egg freezing. I considered not continuing with the cycle, because it didn’t feel like I really needed it.

I strongly recommend that anyone with a possible interest in kids should get their fertility numbers checked, just for your information! Even if you don’t think you want to do egg freezing!

How exactly?

A friend recommended Modern Fertility, which for $159 will walk you through getting a hormone-level blood test done at a Quest Diagnostics lab (or a test you can take at home, that seems to be a finger-prick blood test) and send you an interpretation.

I clicked through the Modern Fertility request-more-information process. It looks like they give you results basically like this, along with a longer explanation of what they mean:

Mason says you can schedule both an ultrasound and a blood test at fertility clinics for $200-400. It’s also the first step of the egg freezing process.

Lesson 3: Consultation → extraction can take a long time, depending on clinic

Here’s what my timeline looked like:

Filled out the interest form with Progyny in August 2018

Had a call with Progyny in October

Initial UCSF doctor consultation in December

Bloodwork in January 2019

Spent February waiting for someone to get back to me, then realizing I had the baton and was supposed to have contacted someone to schedule next steps; finally got in touch with my UCSF coordinator.

Started birth control in March to prepare for an April cycle

Completed my extraction in April 2019

I expected this to be much shorter!

A friend HK had a much, much faster experience working with RMA-NC in San Francisco. They were able to complete extraction just a month and a half after they initially reached out, and less than a month after their initial consultation. See HK’s writeup for more about their experience.

If I were doing this again, I would schedule initial consultations with multiple places, and then see who could get me started soonest. I don’t think the Progyny signup flow made this option salient to me, but other reimbursement methods (such as Carrot) might be more compatible with shopping around at the start.

Lesson 4: You might need multiple cycles

I thought that it was typical and expected to only do one cycle of egg freezing. I was wrong!

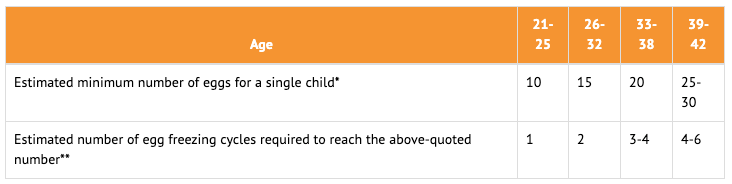

People under 35 can often get away with doing just one cycle to hit their target number of frozen eggs. But if you’re over 35 at the time of freezing your eggs, the target number (to attain a certain probability of later pregnancy) is higher and the yield per cycle is lower.

So there are two contributing factors to needing more cycles with age: reduced quantity and reduced quality.

Quantity (eggs per cycle)

For context: Right after your last period, you normally have a few “resting follicles” that are waiting to participate in the upcoming ovulation cycle.

In a normal menstrual cycle, only one of these available follicles will fully mature in that cycle, and the rest are discarded by the body.

(This means that extraction doesn’t actually decrease the number of available eggs, since they would’ve been expelled anyway. Moreover, at birth ovaries contain 2 million eggs! A few dozen won’t be missed!)

In an egg freezing or IVF cycle, ~all the resting follicles are artificially developed to produce mature eggs.

Active follicle count per cycle goes down with age, which also means that the number of eggs that can be extracted per cycle goes down.

So: If you’re older, it’ll take you more cycles to produce a given target number of frozen eggs.

Quality (target number of eggs)

Additionally, chromosomal abnormalities in the eggs go up with age, so fewer of the eggs you collect are likely to turn into normal embryos.

This means that with increasing age at time of freezing, you need a higher target number of frozen eggs for the same likelihood of successful pregnancy later.

Overall picture

Both factors that increase with age at time of freezing - more cycles for the same target, and a higher target - pull in the direction of needing to do more egg freezing cycles to get the same probability of later pregnancy.

Maybe smaller cycles are less taxing?

Another friend did this process, and had 3-4x fewer eggs than I did, which means she’s likely to do a second cycle. Fortunately, her experience was much milder than mine! She couldn’t feel her ovaries at all even when fully enlarged, and reported the physical symptoms were within variance of a typical period.

It stands to reason that if you only have <10 enlarged follicles instead of >30, the physical impact would be lower. Based on this, I now would weakly anticipate smaller-yield cycles to also be less taxing on average, and thus more approachable to undergo several; albeit with considerable individual variation.

Lesson 5: Freezing eggs is usually an “85% chance of 1 kid” card

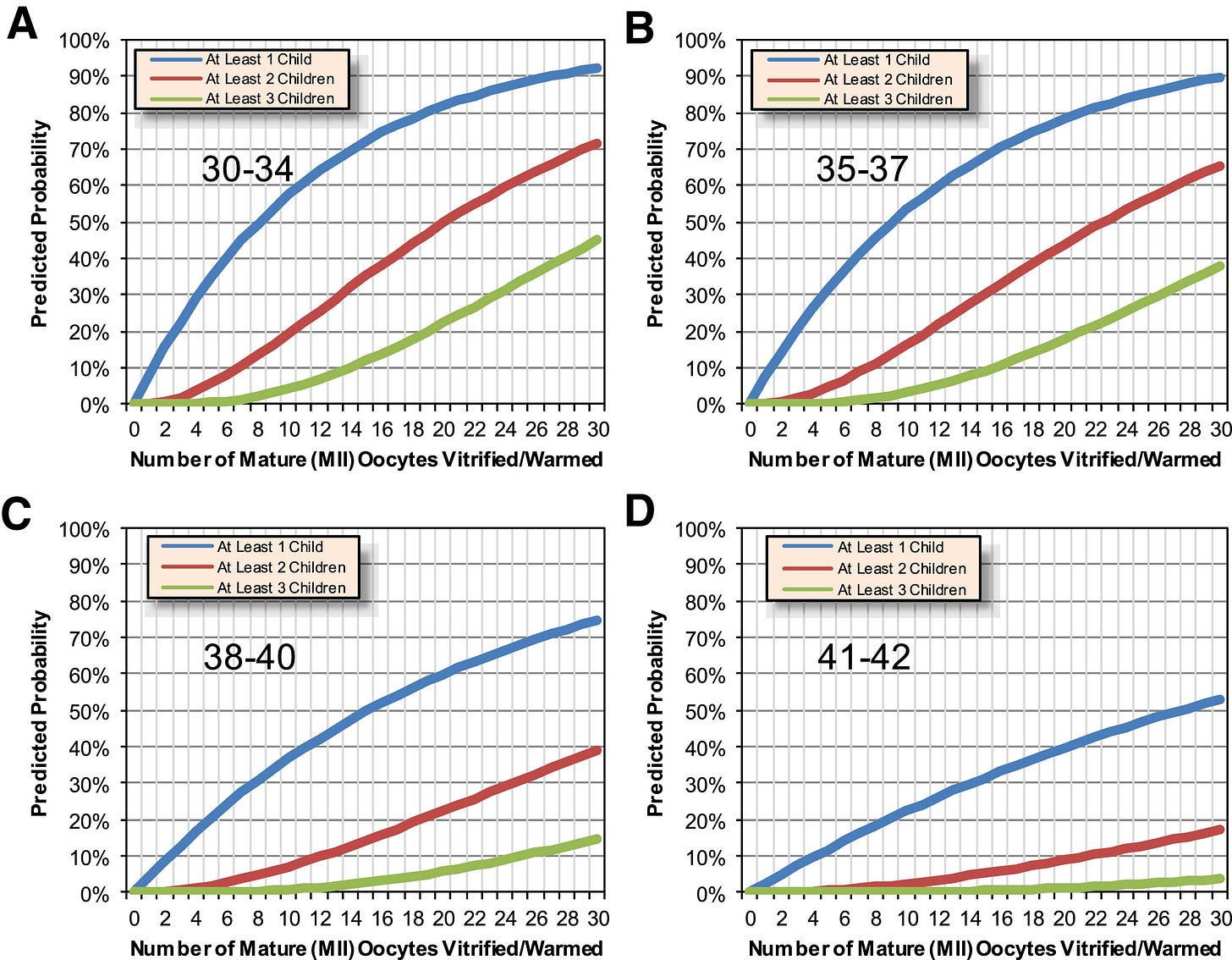

So what are the target numbers of eggs, for what probability of later pregnancy? I really wish I had known these going in.

A rule of thumb for <35-year olds is “15 eggs = 85% chance of 1 kid”

I skimmed a lot of sources, and the picture they paint is broadly similar:

Also check out this calculator! https://www.mdcalc.com/bwh-egg-freezing-counseling-tool-efct#creator-insights

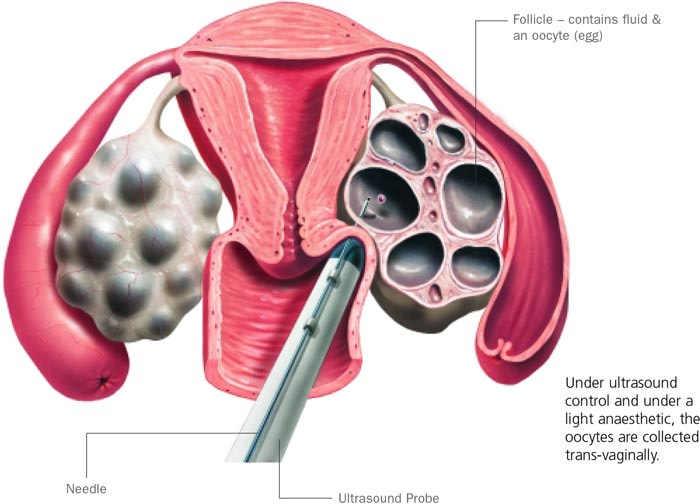

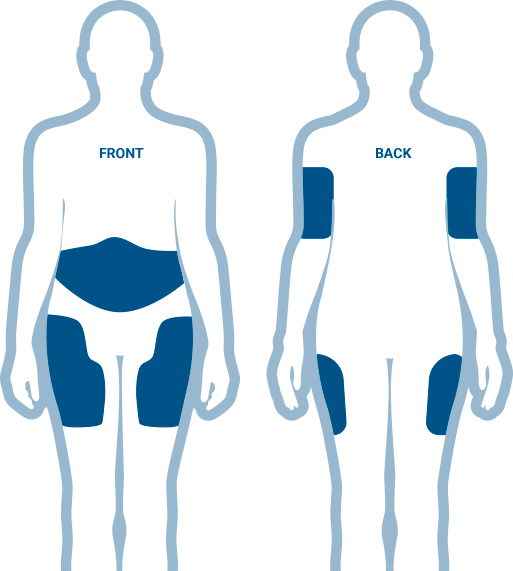

Lesson 6: Ovaries go from walnut- to orange-sized

I knew my ovaries would get larger, but I couldn’t easily find good data about exactly how large we’re talking.

My current understanding is that ovaries are usually the size of a walnut, and when stimulated they each become the size of a small orange:

By day 5 of the stimulating hormones, I could feel where exactly my ovaries were located in my groin area - a strange sensation! On day 7 and 8, it was noticeably uncomfortable to walk: I felt a sensation like tugging on supporting ligaments.

Lesson 7: No strenuous exercise!

Once the ovaries start getting large, the doctors recommend that you avoid high-impact or strenuous exercise, to avoid the risk of the ovaries twisting.

I didn’t realize that the ovaries stay huge all month, even after the extraction, until your next period. Not being able to do strenuous exercise for this long was pretty annoying!

A friend reported that her doctor gave her the OK for her to use an exercise bike as long as she kept her heart rate below a certain number. This makes sense to me: an exercise bike doesn’t seem vastly likely to cause twisting.

Lesson 8: Injections are annoying, but you can do things to make them better

There are three types of subcutaneous injections that you have to give yourself every day. They tell you to do these in the belly, like insulin.

Stimulation

Every evening for 1-2 weeks

I had two shots in this category: Menopur and Gonal-F

Prevent premature ovulation

Starts a few days later, in the morning

I was on a “GnRH antagonist” protocol (explained later) so I took Cetrotide

Trigger shot, to cause the eggs to mature

Just once, after enough follicles are above 13 mm; retrieval is 36 hours later

I had two shots as a dual trigger: Lupron and low-dose hCG

I found these injections annoying for a few reasons:

Mixing and measuring the medication is surprisingly fussy.

The Menopur specifically really stung when it went in (the others were totally fine).

I got bruises on my abdomen at some of the needle sites. Not only painful, but having abdominal bruises really didn’t help me figure out if I was tender because of the shots or because of my ovaries.

I did a few things to make this better:

Apply an ice pack before & after the shots. Really helped with the menopur!

Put the needle in really fast.

Move my injection site to the thigh instead of the belly. They didn’t tell me to do this, but I looked up advice about subcutaneous injections that suggested using different sites. It really helped me to physically separate “my belly hurts from injection bruises” from “my belly hurts because my ovaries are enlarged”

Lesson 9: OHSS is a *fluid balance* problem

The main complication they warn you about is Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS), which can be mild, moderate, or severe (~5%?).

Severe OHSS is the only complication with a risk of significant problems, so I think it’s worth building a good model of what’s going on. Unfortunately, I felt like the doctors never really explained what the actual mechanism is, and just listed a grab-bag of symptoms, which I found unnecessarily confusing.

The mechanism:

=> In severe OHSS, the trigger shot changes the fluid balance of your ovarian tissue, causing fluid to leak into your abdomen.

So the major symptoms to watch out for are fluid balance problems: rapid weight gain (which is all water), increased abdominal girth (also water), difficulty urinating despite the urge, and shortness of breath (from fluid in your abdomen pressing on the lungs).

Relatedly: On the day of my trigger shot, the nurse told me that drinking electrolytes might help. I did this, and… it might’ve helped? I didn’t drink any plain water all day before my retrieval, and instead added nuun tablets to any water I was drinking. I also kept my total fluid intake a bit lower than usual, so I was probably mildly dehydrated (and a bit sleepy), but I didn’t experience any obviously-swelling-related symptoms.

Friends Matt Bell & Helen Lurie corroborate this advice: “Following a protocol of consuming electrolytes daily drastically reduces swelling. Whey protein is recommended as well. We only got this advice this round [out of two rounds], and it seems to have made a big difference.”

Lesson 10: Ask what protocol you’re on!

If you’re at increased risk of OHSS (e.g if you have a lot of follicles, like me) the doctors might choose a different protocol of shots to take: the antagonist protocol instead of the agonist protocol. (Matt Bell reports there’s also a difference between the “short” and “long” agonist protocol, but I don’t know as much about that.)

One change is the drug used for suppression. Using GnRH antagonist (such as Gonal-F) for suppression, instead of an agonist (such as Lupron) causes a 20% reduction in OHSS incidence - substantial, but not definitive. (see the intro / literature review in Lainas et al. 2012)

There’s some evidence that the “antagonist protocol” leads to a reduced birth rate in fresh IVF cycles (where pregnancy comes immediately afterwards), but no change in freeze-all cycles (which is what egg freezing is most like), so there’s no reason to think the antagonist protocol is any worse.

The other change is in the final trigger shot. Using a GnRH agonist trigger (instead of the usual hCG trigger) virtually eliminates OHSS (e.g. zero cases of OHSS in 123 women, Atkinson et al. 2014), which is awesome!

However, using no hCG also decreases the total final yield.

As a compromise between OHSS risk and total yield, my doctor had me do an antagonist protocol with a dual trigger: primarily Lupron, but with a side of the lowest possible dose of hCG. This worked well for me and I didn’t have any even-moderate symptoms.

Ask your doctor!

I wish I had asked more questions earlier about the different possible protocols, my doctor’s decisions, and how he was getting the risk numbers he was telling me about.

When I asked my doctor about agonist/antagonist protocols and risks, he told me 1) that I was on the antagonist protocol, and 2) that my risk of OHSS was “Mild = 100%. Moderate = 50%. Severe = 5%.”

This didn’t make sense to me with what I had read: didn’t the literature show an OHSS-free outcome from Lupron trigger?

Finally when I realized I was going to co-trigger with a small dose of hCG (which is the one with more OHSS risks) in addition to the Lupron, then I was able to get the numbers to line up.

Lesson 11: Minimize commute time to the clinic

You’ll be going to the clinic for frequent morning appointments (every day, or every other day), so reducing commute time to the clinic and then to work afterwards is a very important factor in the overall annoyance!

Lesson 12: You can use COBRA for this if you might change jobs and lose fertility benefits

I started looking into using my Google fertility benefit as soon as I was even vaguely remotely considering leaving Google, but I didn’t finish the process before I left.

That’s OK! If you had fertility benefits with a previous employer, you’re allowed to stay on your old insurance using COBRA, even if you have a new insurance plan at your new employer, in the case where your old plan covers something (fertility!) that your new plan doesn’t.

Lesson 13: You can look up success rates

The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology maintains statistics for established clinics. Newer clinics might not have statistics, but they’re usually still listed as SART members in good standing.

I didn’t use success rates in my decision process because I didn’t know about this website at the time. In retrospect I’m not sure how big a difference it would’ve made, except to confirm that the clinic had rates in the right ballpark. My uncertainty is because different clinics might be drawing from very different populations or have different entry criteria, so you can’t ascribe all the variation in success rates to their techniques and technology.

HK has a spreadsheet here comparing different clinics in SF, linked from HK’s writeup.

Lesson 14: Choose a time window when you can tolerate schedule disruption

Borrowing this directly from HK’s writeup: “I think it's worth being thoughtful about your timing and attentive to the calendar. Once you start a cycle, there are very frequent clinic visits, nightly injections, and surgery could fall anywhere in a ~5-day window, with a few-day recovery. I suggest doing this at a time when it's OK for you to not be at your best and when you don't have unmissable schedule obligations. If you are in a relationship, I suggest applying this to both you and your partner; [my partner] and I felt it was helpful for me to be present for the injections (which are stressful, especially the trigger shot due to the novel mechanics and precise timing), and you'll need to be driven home and accompanied after surgery.”

As a note on being driven home: You also have the option of using a medical pickup service like https://www.silverride.com/medical-pickups/, but you cannot just schedule an Uber. They will not release you from the hospital unless you have a friend or a medical pickup service to pick you up.

This is interesting and has some crossover with lessons for getting pregnant via donor sperm. Two that come to mind:

1. Fertility testing is expensive compared to having sex (free) but cheap compared with one vial of sperm from a sperm bank ($1k). Might as well get a hysterosalpingogram before you get started to make sure your uterus is good to go.

2. Living close to the sperm bank makes it way easier. The sperm vial is tiny, but it comes in a tank of liquid nitrogen that you can strap into the passenger seat of your car. It's heavy, and you have to return it, too. You can save hundreds of dollars on shipping each try by doing the pickup/return yourself.

Also the "no strenuous activity" point applies, but more as a stress thing. Your body's hormonal profile is super important to the whole project.